Shallow vs Deep: A Finance-Oriented View

- Shallow models approximate a relationship like

- Deep models construct

- Benefits in finance:

-

Representation learning: automatically extract latent factors or features (e.g., nonlinear risk factors) from raw inputs.

-

Scalability to high dimension: many parameters but trained with stochastic optimization and regularization.

-

Inductive biases:

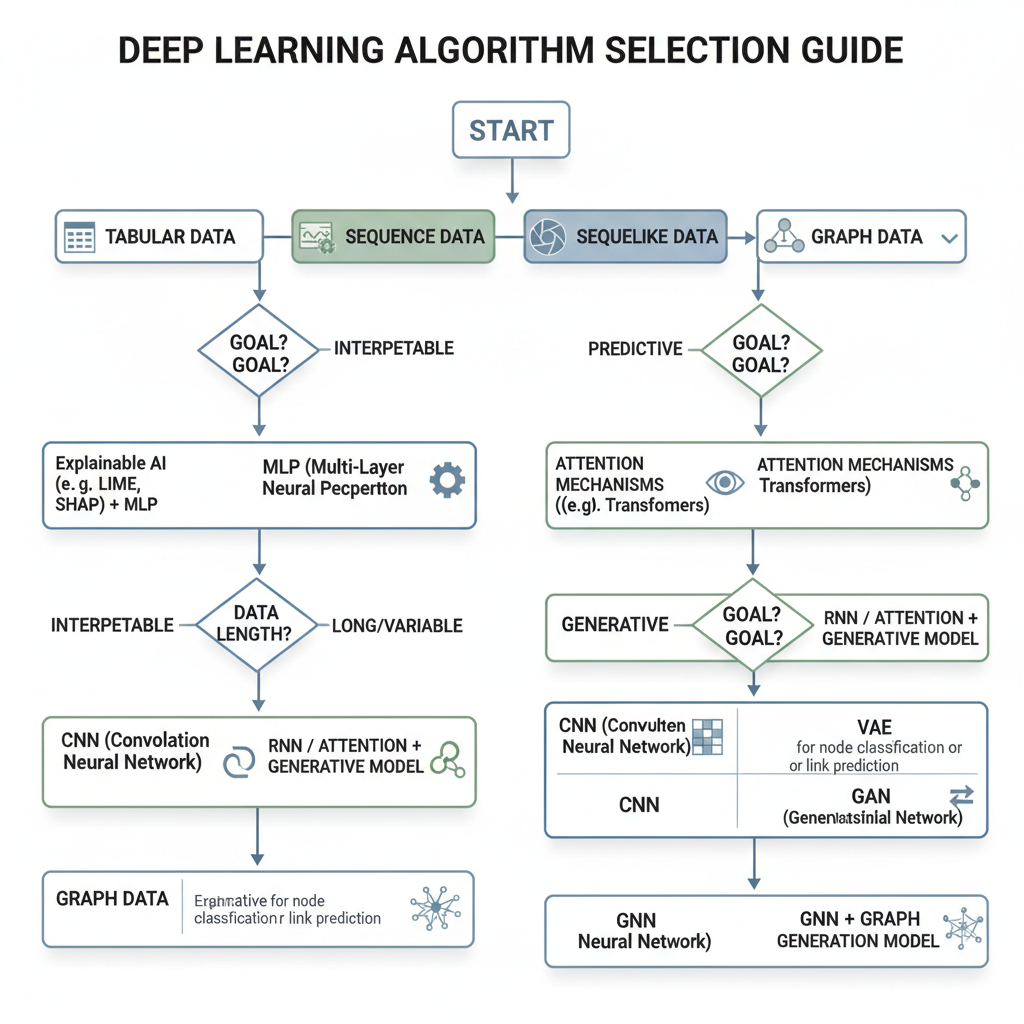

MLP CNN RNN GNN flexible for general tabular data. local patterns and translation invariance (useful for structured signals like term structures or limit order books). sequential dependence in returns, volatility, or flows. relationships on graphs (counterparty, supply-chain, ownership).

-

When Might Deep Models Be Useful?

- Problems that may benefit:

- Highly nonlinear mapping from features to target (e.g., complex interaction among risk factors).

- Large training datasets (long history, cross-section of many assets, rich microstructure data).

- Sequential prediction with long memory (volatility clustering, order book dynamics).

- Networked systems (contagion, systemic risk, linked entities).

- Problems where shallow models are often enough:

- Small samples, few predictors, strong theory-driven structure.

- Tasks dominated by interpretability and regulatory transparency.

- In empirical asset pricing, for example, deep networks can be seen as flexible nonparametric asset-pricing models, estimating:

where - We will treat architectures as a toolkit, not as competitors to theory.

Part 2 · Multilayer Perceptrons (MLP)

Motivation

- MLPs are the basic building block of deep learning.

- They generalize linear regression and logistic regression by adding hidden layers and nonlinear activations.

- Suitable for:

- Tabular financial data: firm characteristics, macro variables, technical indicators.

- Cross-sectional predictions: expected returns, default probabilities, recovery rates.

- Approximating unknown pricing functions or utility functions.

- Conceptually, MLPs implement:

- Before specialized architectures (CNN, RNN, GNN), many financial applications start with MLPs as a baseline deep model.

Neural Network Foundations for This Lecture

- All architectures in this lecture share a common set of foundations:

- From perceptron to MLP: stacking linear units with nonlinear activations to model complex functions.

- Activation functions: sigmoid, tanh, ReLU and its variants, controlling nonlinearity and gradient flow.

- Loss functions: squared error for regression, cross-entropy for classification, plus regularization terms.

- Backpropagation: efficient gradient computation via the chain rule on computation graphs.

- Optimization and initialization: stochastic gradient methods and suitable initial weights to mitigate vanishing/exploding gradients.

- Once these foundations are in place, different architectures mainly differ in how they connect units and what structure they impose on the data.

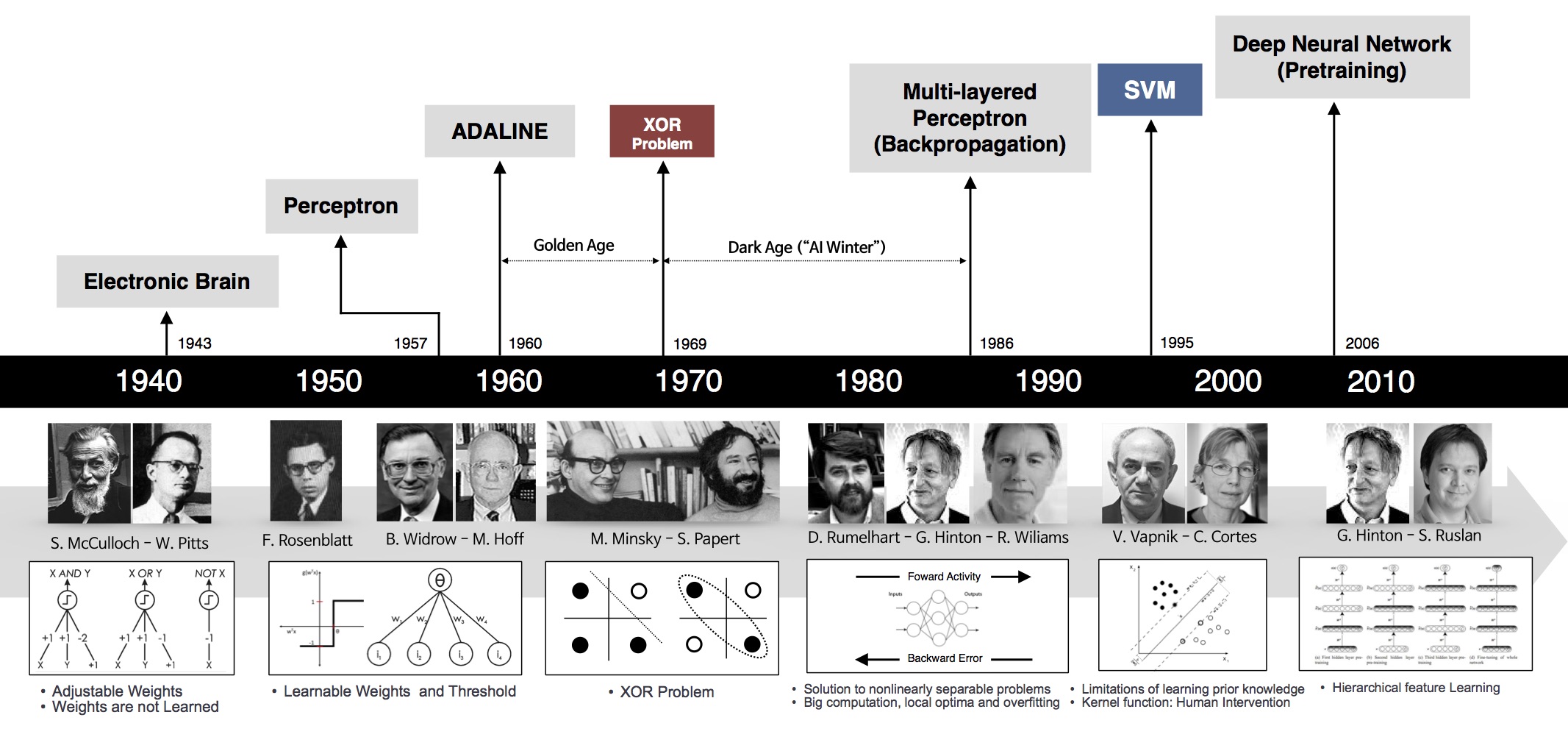

A Brief History of Neural Networks

- 1940s–1950s: Early neuron models (McCulloch–Pitts) and Hebbian learning provided the first abstraction of neurons and synapses.

- 1958: Rosenblatt’s perceptron showed that simple networks can learn linear decision boundaries, raising optimism about artificial intelligence.

- 1969: Minsky & Papert demonstrated that single-layer perceptrons cannot solve linearly inseparable problems such as XOR. This contributed to the first “AI winter”.

- 1980s: The backpropagation algorithm for multilayer networks was popularized, showing that deeper networks can be trained by gradient descent.

- 1990s–2000s: SVMs and other “shallow” methods dominated practical applications due to better theory and optimization.

- 2010s: Deep learning resurged, powered by GPUs, large datasets, and improved architectures (CNN, RNN, residual networks), and is now mainstream in many domains including finance.

The Perceptron and Its Limitation

- A perceptron computes

corresponding to a linear decision boundary in the input space. - Geometrically, it classifies points by which side of a hyperplane they lie on. If two classes are linearly separable, a perceptron can find such a hyperplane.

- However, many relevant problems are not linearly separable. The classic example is the XOR function on two binary inputs:

- XOR is 1 if exactly one of the inputs is 1, and 0 otherwise.

- In 2D space, the positive and negative points cannot be separated by any straight line.

- This limitation illustrates why single-layer networks are insufficient and motivates adding hidden layers with nonlinear activations.

Solving XOR with a Small MLP

- A two-layer MLP can implement XOR by introducing hidden units that form intermediate nonlinear features.

- One construction:

- Hidden unit 1 learns something similar to an OR pattern of the two inputs.

- Hidden unit 2 learns something similar to an AND pattern.

- The output neuron then combines these hidden activations to produce XOR.

- Conceptually, the hidden layer performs a nonlinear transformation that makes the problem linearly separable in the hidden space.

- This example illustrates the power of depth:

- Shallow linear models cannot solve XOR.

- A small network with one hidden layer can represent more complex decision regions, even with few parameters.

Neuron, Layer, Network

|

|

Application · Empirical Asset Pricing via ML (Gu, Kelly & Xiu, 2020, RFS)

- Problem

- Canonical question: how to predict the cross-section of next-period stock returns from a very large set of firm characteristics, and assess the economic value of such predictions.

Xit

")] Model[["MLP / Other ML"]] Pred["E[Ri,t+1 | Xit]

(Expected Returns)"] App["Portfolio Sorting

& Performance"] %% 流程连接:使用粗箭头强调数据流,细箭头强调逻辑流 Input ==> Model Model ==> Pred Pred --> App %% 样式设置:区分不同阶段 %% 蓝色:数据输入 style Input fill:#e3f2fd,stroke:#1565c0,stroke-width:2px %% 紫色:模型计算 style Model fill:#f3e5f5,stroke:#7b1fa2,stroke-width:2px,rx:5 %% 绿色:预测结果 style Pred fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#2e7d32,stroke-width:2px %% 橙色:应用策略 style App fill:#fff3e0,stroke:#ef6c00,stroke-dasharray: 5 5

- Model / Algorithm

- Compare linear OLS and regularized linear models (Ridge, Lasso, Elastic Net) with nonlinear ML, including random forests, gradient boosting, and deep feedforward neural networks (MLPs).

- Deep MLPs: several fully connected layers with nonlinear activations, trained by stochastic gradient descent with regularization and early stopping.

- Key Results

- Many ML methods—including deep nets—deliver substantially better out-of-sample performance than traditional linear factor models, both statistically and economically (Sharpe ratios, portfolio alphas).

- Improvements are especially pronounced when using the full, large characteristic set instead of a few “hand-picked” factors.

- Why suitable here

- Data are high-dimensional tabular

- The paper provides a clean, large-sample benchmark for when deep and other ML methods pay off in empirical asset pricing.

- Data are high-dimensional tabular

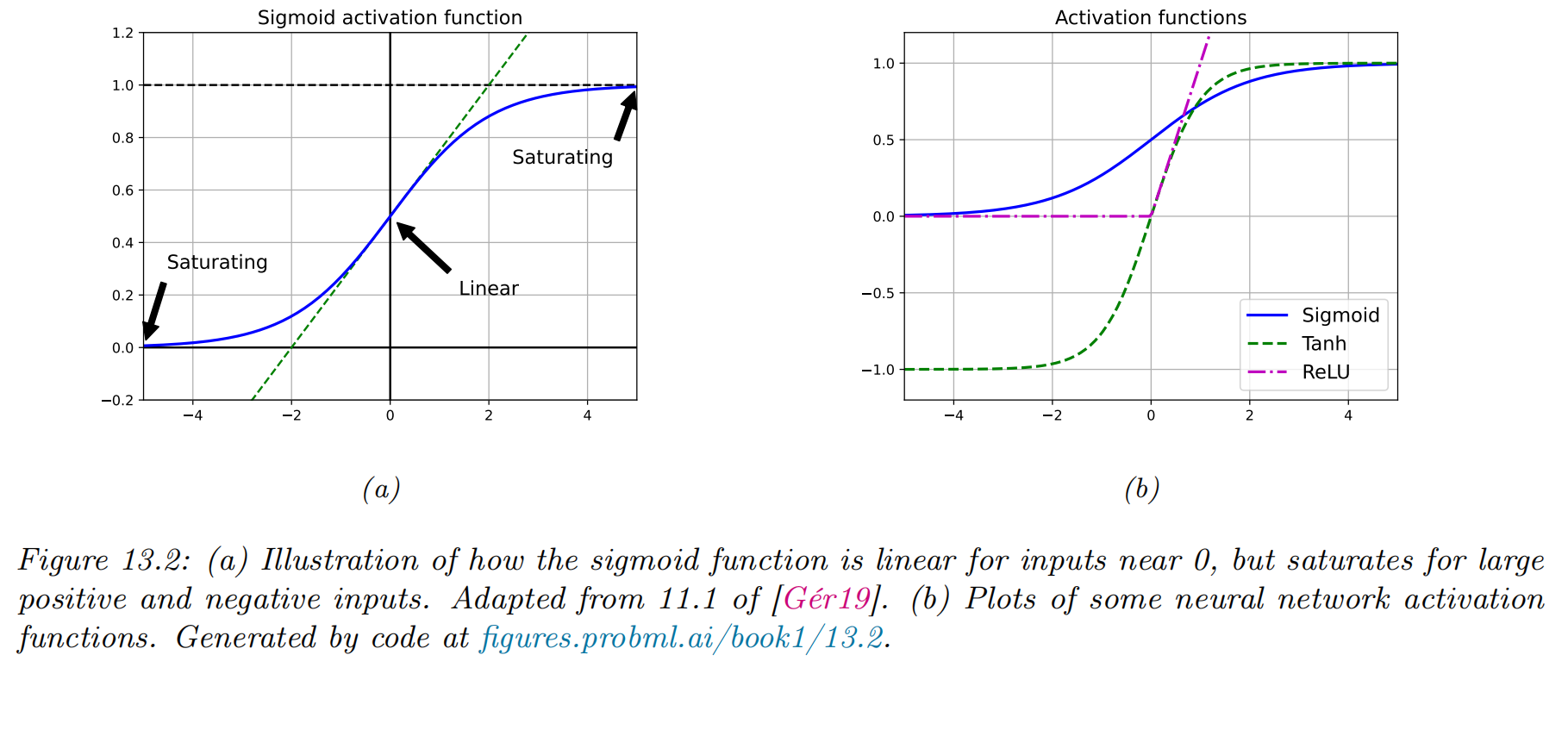

Sigmoid and Tanh: Saturating Activations

- Two classical activation functions are:

- Sigmoid:

- Tanh:

- Sigmoid:

- Advantages:

- Smooth and differentiable everywhere.

- Naturally map pre-activations to bounded ranges, which is useful when modeling probabilities or normalized signals.

- However, for large

- Derivatives

- During backpropagation, gradients multiplied through many such layers tend to vanish, making deep networks hard to train.

- Derivatives

- As a result, modern deep networks rarely use sigmoid/tanh in hidden layers, except in specific architectures such as LSTM gates.

ReLU and Its Variants

- The Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) is defined as

- Advantages:

- Non-saturating for positive

- Computationally simple and works well in practice for many deep networks.

- Non-saturating for positive

- Drawbacks:

- For

- For

- Common variants try to mitigate dead neurons:

- Leaky ReLU:

- Parametric ReLU (PReLU): learnable negative slope.

- Leaky ReLU:

- In deep MLPs and CNNs, ReLU and its variants are usually the default choice for hidden layers due to good optimization properties.

Beyond ReLU: Smooth and Self-Gated Activations

- Several activation functions extend ReLU to improve smoothness or adaptivity:

- ELU (Exponential Linear Unit): behaves like ReLU for positive

- SELU (Scaled ELU): designed to encourage self-normalizing properties in certain architectures.

- GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit): multiplies inputs by a smooth gating function

- Swish / SiLU:

- ELU (Exponential Linear Unit): behaves like ReLU for positive

- These functions are smooth and often yield slightly better empirical performance than plain ReLU in some settings.

- In finance applications, the exact choice among ReLU-like activations is usually less important than data quality, regularization, and model validation, but understanding their behavior helps diagnose training issues.

Loss and Training Objective

- For regression (e.g., return prediction):

- For binary classification (e.g., default/no default):

with - Often add regularization:

- Training problem:

solved by (stochastic) gradient-based optimization (SGD, Adam, etc.). - This is conceptually similar to penalized regression (L02), but with a much richer model class.

Example models

|

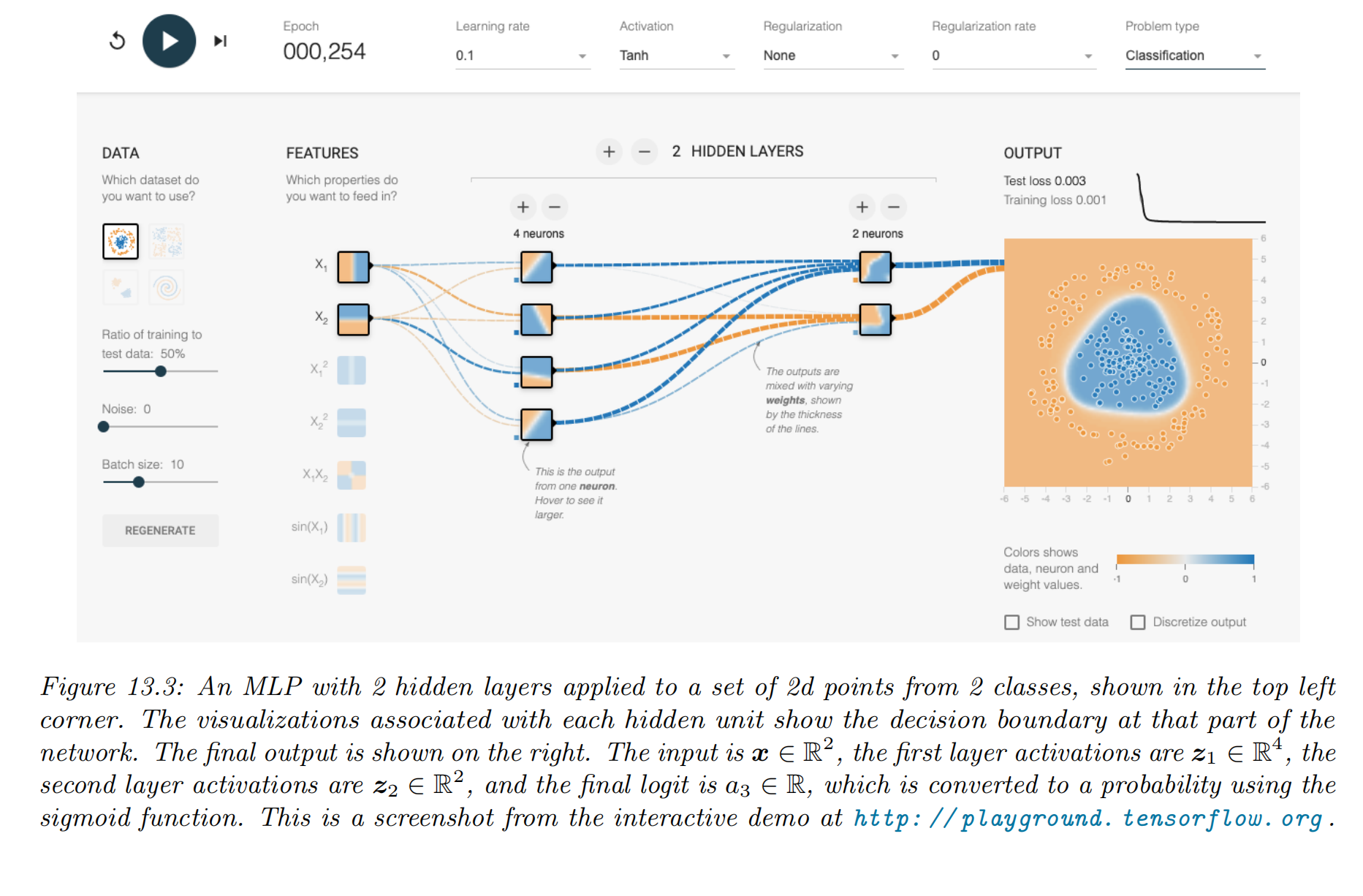

MLPs can be used to perform classification and regression for many kinds of data. We give some examples below. Try it for yourself via: https://playground.tensorflow.org |

Intuition and Universal Approximation

- An MLP effectively performs learned feature transformations layer by layer:

- Hidden units can be viewed as learned basis functions:

- In linear regression with basis expansion we choose basis functions manually.

- In MLP, basis functions are learned from data.

- Universal Approximation Theorem (informal):

- A feedforward network with one hidden layer and sufficient units, using a non-polynomial activation (e.g., sigmoid, ReLU), can approximate any continuous function on a compact set to arbitrary accuracy.

- Deeper networks can approximate some functions more parameter-efficiently than shallow, very-wide ones.

- For finance:

- Think of MLPs as flexible nonparametric estimators of conditional expectations or pricing kernels, with internal structure that may align (or not) with economic theory.

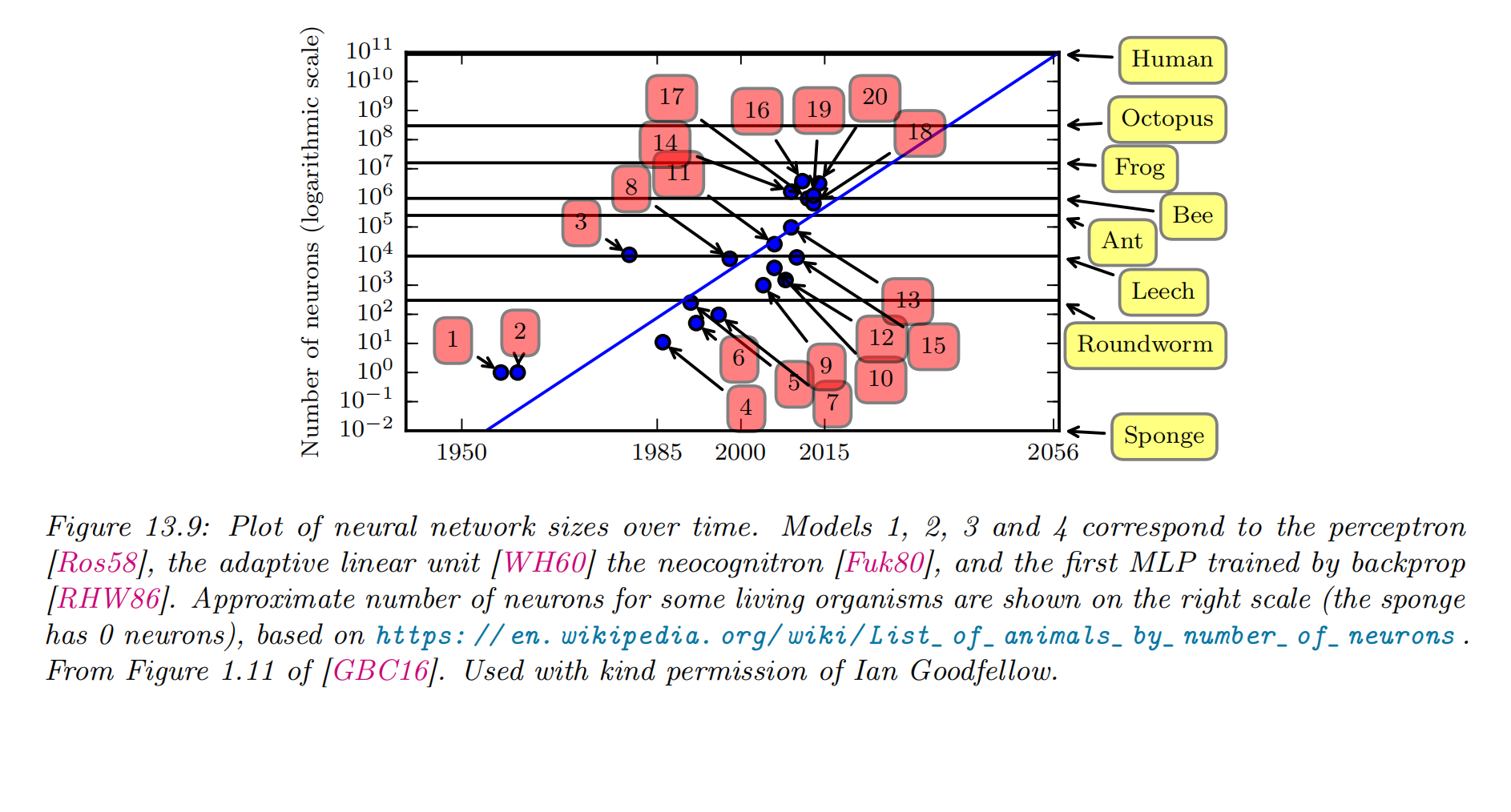

The "deep learning revolution"

- some successful stories about DNNs

- automatic speech recognition (ASR)

- ImageNet image classification benchmark: reducing the error rate from 26% to 16% in a single year

- The “explosion” in the usage of DNNs

- the availability of cheap GPUs (graphics processing units)

- the growth in large labeled datasets

- high quality open-source software libraries for DNNs

- Tensorflow (made by Google)

- PyTorch (made by Facebook)

- MXNet (made by Amazon)

- PaddlePaddle 飞桨 (百度)

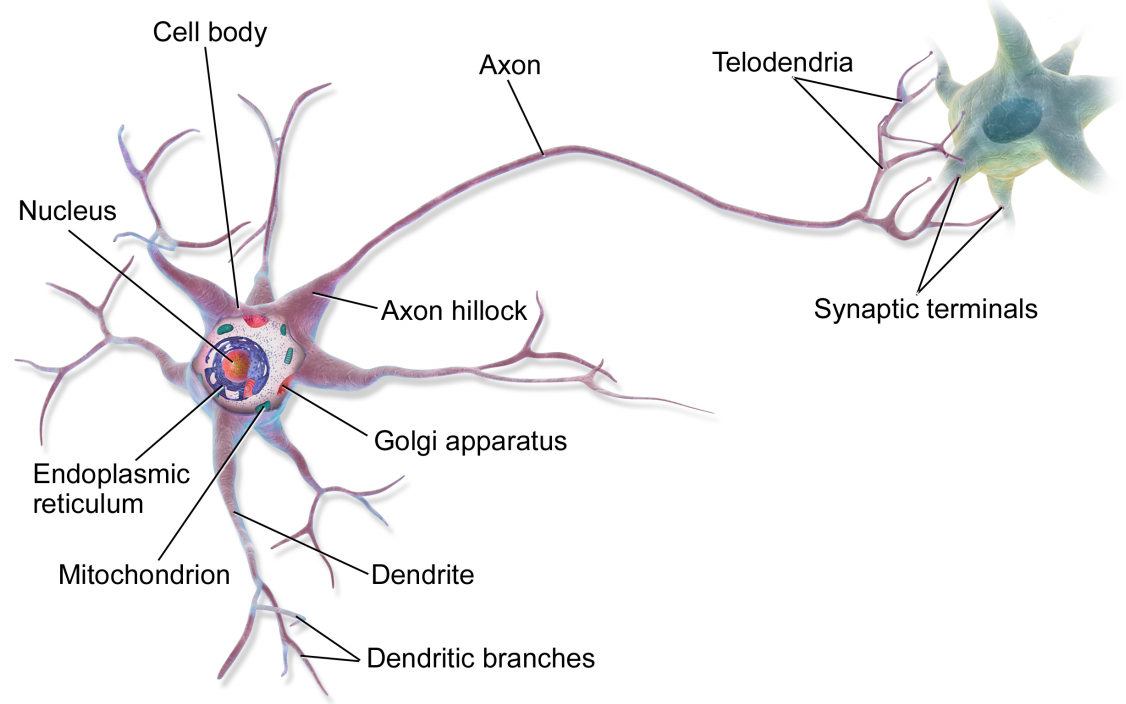

Connections with biology

|

|

- ANNs differs from biological brains in many ways, including the following:

- Most ANNs use backpropagation to modify the strength of their connections while real brains do not use backprop

- there is no way to send information backwards along an axon

- they use local update rules for adjusting synaptic strengths

- Most ANNs are strictly feedforward (前馈的), but real brains have many feedback connections

- It is believed that this feedback acts like a prior

- Most ANNs use simplified neurons consisting of a weighted sum passed through a nonlinearity, but real biological neurons have complex dendritic tree structures (see Figure 13.8), with complex spatio-temporal dynamics.

- Most ANNs are smaller in size and number of connections than biological brains

- Most ANNs are designed to model a single function while biological brains are very complex systems that implement different kinds of functions or behaviors

Training Procedure (Backpropagation): High-Level Steps

- Initialization

- Initialize weights

- Initialize weights

- Forward pass

- For each layer

- Compute pre-activation

- Compute activation

- Compute pre-activation

- Obtain prediction

- For each layer

- Backward pass (backpropagation)

- Compute gradient of loss at output

- For layers

- Compute gradients

- Compute gradient of loss at output

- Parameter update

- Use optimizer (e.g., SGD, Adam) to update all parameters.

Computation Graph View of Backprop

- A neural network can be viewed as a directed acyclic graph (computation graph):

- Nodes represent intermediate variables (e.g., pre-activations

- Edges represent elementary operations such as addition, multiplication, or applying an activation function.

- Nodes represent intermediate variables (e.g., pre-activations

- During the forward pass, we:

- Traverse the graph from inputs to outputs.

- Compute and store intermediate values at each node.

- During the backward pass, we:

- Traverse the graph in reverse topological order.

- Use the chain rule to compute gradients of the loss with respect to each node.

- For a node with multiple outgoing edges, its gradient is the sum of contributions from all downstream paths.

- Modern deep learning frameworks (PyTorch, TensorFlow) implement this as automatic differentiation, building and traversing computation graphs automatically.

Pros, Cons, and Finance Use Cases

Pros vs Cons

| Aspect | Pros | Cons / Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Flexibility | Universal approximator, rich nonlinearities | Easy to overfit with small samples |

| Data format | Works well on tabular, cross-sectional data | No built-in inductive bias for sequence/graph |

| Optimization | SGD-based training scales to large datasets | Nonconvex; local minima, saddle points |

| Interpret. | Can embed economic constraints via architecture | Harder to explain than linear / trees |

- Typical finance applications:

- Cross-sectional asset pricing: predicting expected returns from many characteristics and macro signals.

- Credit risk: nonlinear default probability models.

- Risk management: mapping many risk factors into portfolio loss distributions.

- In practice, MLPs are often the baseline deep model before trying more specialized architectures.

Summary

- MLPs are the canonical deep learning architecture for structured tabular data.

- They generalize linear models by stacking multiple affine transformations and nonlinear activations.

- The training objective combines a data-fitting loss (squared error, cross-entropy) with regularization, optimized by stochastic gradient methods.

- Intuitively, hidden layers implement learned basis expansions and representation learning.

- In finance, MLPs are useful for high-dimensional, nonlinear prediction problems, especially when we have relatively large datasets.

- Limitations include potential overfitting, lower interpretability, and lack of inductive bias for sequences or networks, which motivates CNNs, RNNs, and GNNs.

Application · Autoencoder Asset Pricing Models (Gu, Kelly & Xiu, 2021, JoE)

- Problem

- Construct an asset pricing factor model without assuming linear factors or linear loadings: learn latent market states and their (possibly nonlinear) effects on a large cross-section of returns.

- Model / Algorithm

- Use a deep autoencoder on panels of returns:

- Encoder

- Decoder

- Encoder

- Train by minimizing reconstruction error with regularization; compare to PCA and linear factor models.

- Use a deep autoencoder on panels of returns:

- Key Results

- Autoencoder factors explain a large share of return covariance and pricing errors, and can capture structures that linear PCA-based factors miss.

- The learned latent factors can be linked a posteriori to economically interpretable patterns, but are not constrained to standard linear forms.

- Why suitable here

- The task is essentially nonlinear dimension reduction of returns → canonical use case for autoencoders.

- Autoencoders generalize PCA: treat traditional linear factor models as a special case, and provide a natural bridge to VAEs and other generative latent-variable models.

Application · Deep Learning in Asset Pricing (Chen, Pelger & Zhu, 2023, MS)

- Problem

- Develop a unified framework where deep learning models the stochastic discount factor (SDF) / expected returns from many characteristics, and study when/why deep architectures outperform classical models.

+

Macro Factors"] DeepNet[["Deep Neural Network

(Estimation)"]] Output["SDF (Mt+1)

/

Expected Return"] Condition["Pricing Errors

/

Moment Conditions"] %% 流程连接 Input ==> DeepNet DeepNet ==> Output Output --> Condition %% 样式美化 %% 蓝色:输入数据 style Input fill:#e3f2fd,stroke:#1565c0,stroke-width:2px %% 紫色:黑箱/深度网络 style DeepNet fill:#f3e5f5,stroke:#7b1fa2,stroke-width:2px,rx:5 %% 绿色:核心输出 (SDF) style Output fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#2e7d32,stroke-width:2px %% 红色/橙色:误差与检验 style Condition fill:#ffebee,stroke:#c62828,stroke-dasharray: 5 5

- Model / Algorithm

- Parameterize the SDF or conditional mean as a deep network of firm characteristics and macro variables, mainly using multi-layer MLPs with carefully chosen depth/width and regularization.

- Impose economically motivated constraints (e.g., no-arbitrage) and use cross-sectional moment conditions to train the network.

- Key Results

- Deep SDFs substantially improve pricing accuracy and out-of-sample performance relative to traditional linear factor models and simpler ML.

- Learned “factors” and exposures can be related back to known characteristics, providing economic interpretation despite the black-box architecture.

- Why suitable here

- Asset pricing with many characteristics and nonlinear risk-return tradeoffs is exactly the regime where deep MLPs provide flexible, high-capacity function classes.

- The paper shows how to embed deep nets in a structural SDF / moment condition framework, complementing purely predictive uses of ML.

Part 3 · Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

Motivation

- Many financial inputs are ordered or grid-like: yield curves across maturities, limit order books across price levels, time series of features across short horizons.

- A fully connected MLP ignores this structure and treats all input dimensions as exchangeable.

- CNNs introduce an architectural inductive bias:

- Local connectivity: each unit looks only at a local neighborhood.

- Weight sharing: the same filter is applied across positions.

- As a result, CNNs specialize in learning local patterns and translation-invariant features.

- For finance, this makes CNNs natural for:

- Detecting local shapes in term structures or volatility surfaces.

- Extracting patterns from high-frequency signals or stacked microstructure features.

- We will mainly focus on 1D convolutions suitable for time-series–like financial data.

1D Convolution Formulation

- Consider a 1D input sequence

- A 1D convolution with filter

- With multiple filters, we get feature maps:

- A CNN layer:

- Convolution (or cross-correlation in implementations).

- Nonlinearity

- Optionally pooling (max/average over small windows) to aggregate and downsample.

- Key difference vs MLP: Same filter

1D Convolution as Filtering

- A 1D convolution layer can be interpreted as applying a digital filter to a time series or ordered sequence.

- Example filters:

- Moving average filter

- Difference filter

- Moving average filter

- In a CNN, filter weights are learned from data rather than hand-designed:

- Some filters may become similar to trend detectors.

- Others may detect sharp jumps, volatility bursts, or local patterns in spreads.

- This “learned filtering” perspective is useful when thinking about financial time series:

- Convolutional layers can automatically learn to extract trend, seasonality, and anomaly patterns that are predictive for returns or risk.

Stride, Padding, and Convolution Types

- Stride controls how far we move the filter each step:

- Stride 1: evaluate at every position.

- Stride

- Padding controls how we treat boundaries:

- “Valid” convolution: no padding; output is shorter than input.

- “Same” convolution: pad input so that output has roughly the same length as input.

- “Full” convolution: pad more extensively so filters can fully overlap even at extremes.

- In financial applications:

- Using same padding with stride 1 preserves time alignment, convenient for forecasting tasks.

- Larger strides can be used to coarsen the time resolution, but may discard fine-grained information.

Intuition and Architecture

- Intuition:

- Filters act as pattern detectors that scan over the sequence.

- Lower layers detect local patterns (e.g., short-term fluctuations, local term-structure shapes).

- Higher layers combine them into more abstract patterns.

Multi-channel Time Series"] Conv1["Conv1

1D Convolution

(C1 channels)"] Conv2["Conv2

1D Convolution

(C2 channels)"] Flat["Flatten

(Time × Channels → Vector)"] FC["FC Layer

(Fully Connected)"] Output["Output

Prediction / Score"] %% ---- 数据流 ---- Input --> Conv1 --> Conv2 --> Flat --> FC --> Output %% ---- 样式定义 ---- %% 输入 / 输出:蓝色 classDef io fill:#e3f2fd,stroke:#1565c0,stroke-width:2px; %% 卷积层:紫色 classDef conv fill:#f3e5f5,stroke:#7b1fa2,stroke-width:2px; %% 展平层:浅绿色 classDef flat fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#2e7d32,stroke-width:2px; %% 全连接层:橙色 classDef fc fill:#fff3e0,stroke:#ef6c00,stroke-width:2px; %% ---- 应用样式 ---- class Input,Output io; class Conv1,Conv2 conv; class Flat flat; class FC fc;

- A simple 1D CNN architecture for financial time series:

- Input: sequence of features

- One or more convolutional layers with small kernels (e.g., width 3–5).

- Nonlinearity and possibly pooling.

- Flatten and feed into an MLP for final prediction (regression/classification).

- Input: sequence of features

- Compared with MLP:

- Fewer parameters for the same input length (due to sharing).

- Built-in assumption: nearby positions are more related than distant ones.

Pros, Cons, and Finance Use Cases

Pros vs Cons

| Aspect | Pros | Cons / Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Inductive | Captures local patterns, translation invariance | Less suitable if no local structure |

| Efficiency | Fewer parameters than dense layers | Architecture choices can be ad-hoc |

| Data types | Works well on sequences and grids | May need many filters/levels |

| Interpret. | Filters sometimes interpretable as “motifs” | Still less transparent than linear |

- Finance-oriented uses:

- Term structures (yields, implied volatilities) treated as 1D signals over maturities.

- High-frequency data: price/volume/imbalance across short horizons.

- Limit order books: 2D-like structure (price levels × time) that can be processed with 1D or 2D convolutions.

- CNNs often serve as a front-end feature extractor, with an MLP on top.

From Feature Maps to Feature Maps

- CNNs operate on tensors of feature maps:

- Input to a 1D CNN layer can be viewed as a tensor of shape

- The layer contains filters of shape

- Input to a 1D CNN layer can be viewed as a tensor of shape

- If we have

- Each filter produces one feature map.

- Stacking convolutional layers:

- Earlier layers detect simple local patterns.

- Deeper layers combine them into more abstract representations.

- This “feature maps to feature maps” view parallels factor models in finance, but factors here are nonlinear and learned, not linear combinations specified ex ante.

Pooling Layers

- Pooling layers aggregate features over local neighborhoods, typically by max or average operations:

- Max pooling: takes the maximum value within a window.

- Average pooling: takes the mean value within a window.

- Purposes:

- Introduce invariance to small shifts or noise in the input.

- Reduce the spatial or temporal resolution, lowering the number of parameters and computations in deeper layers.

- In financial time series:

- Pooling can aggregate information over short horizons, focusing on the strongest local signals or average behavior.

- However, excessive pooling can remove useful fine-grained patterns.

- Pooling is often combined with convolutions and followed by fully connected layers for final prediction.

Historical CNN Architectures (Very Brief)

- Several influential CNN architectures shaped modern deep learning:

- LeNet-5: early CNN for digit recognition, demonstrating the power of convolutions and pooling.

- AlexNet: deeper network trained on GPUs, popularized ReLU and large-scale image classification.

- Inception (GoogLeNet): used parallel filters of different sizes, reducing parameters via

- ResNet: introduced residual connections to train very deep networks.

- For this course, we do not focus on image benchmarks, but:

- These architectures motivated many design patterns (e.g., deep stacks, residual blocks) that are now applied to time series and tabular data as well.

- Residual ideas are particularly relevant for improving optimization in deep financial models (see Part 8).

Summary

-

CNNs introduce local receptive fields and parameter sharing, making them efficient for data with spatial or temporal structure.

-

1D convolutions are natural for time-series–like financial inputs, where nearby time points or maturities are strongly related.

-

A typical architecture stacks multiple convolutional layers and then uses fully connected layers for final predictions.

-

CNNs can be viewed as learned filters that detect recurring motifs in financial signals.

-

Limitations arise when the problem does not exhibit clear local patterns, or when long-range dependencies dominate, which motivates RNNs and attention.

-

More broadly, CNNs illustrate how network structure shapes what is easy to learn: with convolutional structure, the model is biased toward learning local, translation-invariant features.

Application · (Re-)Imag(in)ing Price Trends (Jiang, Kelly & Xiu, 2023, JF)

- Problem

- Revisit trend-based predictability by letting a model discover return-predictive price patterns, instead of pre-specifying momentum or reversal rules.

- Use stock-level price charts as inputs and test whether machine-learned patterns beat standard trend signals.

+ Volume

(1D Data)"] %% 2. 图像化 (核心步骤) %% 使用 {{ }} 形状代表“准备/转换”过程 ImgGen{{"TimeSeries

to

Image"}} %% 图像数据的抽象表示 ImgData[("2D Image

(e.g. GAF/RP)")] %% 3. 模型 %% 使用 [[ ]] 代表黑箱/计算密集型模型 CNN[["2D CNN

(Spatial Pattern)"]] %% 4. 预测信号 %% 使用 (( )) 代表单个数值输出 Prob(("P(Up)

Probability")) %% 5. 金融应用 Sorts["Decile Sorts

(Long/Short)"] Perf["Performance

(Sharpe / Alpha)"] %% =========================== %% 流程连接 %% =========================== %% 数据流:粗箭头 RawData ==> ImgGen ImgGen ==> ImgData ImgData ==> CNN CNN ==> Prob %% 策略流:细箭头 Prob --> Sorts Sorts --> Perf %% =========================== %% 样式美化 %% =========================== %% 原始数据:蓝色 style RawData fill:#e3f2fd,stroke:#1565c0,stroke-width:2px %% 图像转换部分:青色/视觉感 style ImgGen fill:#e0f7fa,stroke:#006064,stroke-dasharray: 5 5 style ImgData fill:#b2ebf2,stroke:#006064,stroke-width:2px %% 深度学习:紫色 style CNN fill:#f3e5f5,stroke:#7b1fa2,stroke-width:2px,rx:5 %% 信号:黄色/高亮 style Prob fill:#fff9c4,stroke:#fbc02d,stroke-width:2px %% 回测应用:绿色 style Sorts fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#2e7d32 style Perf fill:#c8e6c9,stroke:#2e7d32,stroke-width:2px

- Model / Algorithm

- Convert recent daily OHLC prices, volume, and moving averages (over 5, 20, 60 days) into black–white images (OHLC bars + MA line + volume bars) with standardized vertical scaling.

- Train 2D CNNs to classify whether the future return over the next 5/20/60 days is positive or not, using cross-entropy loss and standard CNN components (conv–activation–pooling, batch norm, dropout).

- Key Results

- Sorting stocks into deciles by CNN “up” probability yields very high out-of-sample Sharpe ratios (e.g. equal-weight weekly long–short up to ≈7, value-weight ≈1.5), far above momentum or short-term reversal benchmarks.

- CNN forecasts are only weakly correlated with existing technical indicators and firm characteristics; controlling for these, CNN-based signals remain strongly predictive.

- Patterns transfer well across horizons and to international markets: U.S.-trained CNNs applied directly overseas still generate strong Sharpe ratios, often outperforming locally trained models.

- Why suitable here

- Price charts are inherently image-like with local geometric shapes, volatility ranges, and joint price–volume structure; CNNs are built for such 2D local/translation-invariant features.

- The paper shows how image-based CNNs provide a rigorous, scalable implementation of technical analysis, identifying patterns beyond simple momentum/reversal.

Case Study · Charting by Machines (Murray, Xia & Xiao, 2024, JFE)

- Problem

- Test weak-form market efficiency by asking whether only 12 months of price-path information (coarse “chart”) contain economically meaningful predictability in the cross-section of U.S. stock returns (1927–2022).

(Length = 12)"] %% 2. CNN 部分 (特征提取) subgraph Spatial_Block [Spatial Feature Extraction] direction TB Conv["Conv1D Layer

(Filters sliding)"] Pool["(Optional)

Pooling"] end %% 3. 中间特征序列 (桥梁) %% 形状变化示意:长度变短,维度变深 FeatSeq[("Feature Sequence

(Abstracted Time Series)")] %% 4. LSTM 部分 (时序建模) LSTM[["LSTM Layer

(Sequential Processing)"]] %% 5. 输出 Output(("Output

Prediction")) %% --- 连接 --- Input ==> Conv Conv --> Pool Pool ==> FeatSeq FeatSeq ==> LSTM LSTM --> Output %% --- 样式美化 --- %% 输入:蓝色 style Input fill:#e3f2fd,stroke:#1565c0,stroke-width:2px %% CNN 块:紫色系,代表计算/提取 style Conv fill:#f3e5f5,stroke:#8e24aa style Pool fill:#f3e5f5,stroke:#8e24aa,stroke-dasharray: 5 5 style Spatial_Block fill:#fafafa,stroke:#bdbdbd,stroke-dasharray: 5 5 %% 特征序列:橙色,代表中间状态的数据 style FeatSeq fill:#fff3e0,stroke:#ef6c00,stroke-width:2px %% LSTM:绿色,代表记忆/时序 style LSTM fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#2e7d32,stroke-width:2px,rx:5 %% 输出:红色/高亮 style Output fill:#ffebee,stroke:#c62828,stroke-width:2px

- Model / Algorithm

- Input: 12 monthly cumulative excess returns (shape of the 1-year price path).

- Architecture: CNN + LSTM (CNNLSTM) – CNN learns local shape filters along the 12-month path; LSTM captures how these shapes interact over time.

- Target: normalized rank of next-month excess return; loss: MSE with equal stock and time weights to focus on cross-sectional prediction.

- Key Results

- Sorting stocks by the CNNLSTM forecast

- Alphas remain large relative to CAPM, FF, Carhart, FF5, and Q factors; more than half of the variation and predictive power comes from nonlinear interactions across months, not explainable by any linear or simple nonlinear functions of the 12 returns.

- Predictive relations are very stable over time; even a model trained only on pre-1963 data performs strongly in 2015–2022.

- Sorting stocks by the CNNLSTM forecast

- Why suitable here

- The 12-point path is a 1D sequence with local shapes + sequential dependence → natural for CNN filters plus recurrent aggregation.

- The study shows that machine-learned chart patterns contain information beyond momentum, reversal, and known technical indicators, providing a disciplined test of technical analysis in an asset-pricing setting.

Part 4 · Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN, LSTM, GRU)

Motivation

- Many financial problems are fundamentally sequential:

- Asset returns, volatility, liquidity, and order flow evolve over time.

- Macro variables, credit indicators, and risk measures follow dynamic paths.

- Standard MLPs and CNNs do not maintain an explicit state across arbitrary sequence length.

- RNNs introduce a recurrent structure:

- A hidden state

- This allows the network to accumulate information over time and condition predictions on history.

- A hidden state

- In other words, the architecture encodes the assumption that order and temporal dependence matter.

- LSTM and GRU refine this idea with gating mechanisms to better capture medium- and long-term dependencies in financial time series.

From Feedforward to Time Delay to Recurrent

- Feedforward networks (FFNNs) take a fixed-size input vector and produce an output, with no explicit notion of time.

- For sequence data, a simple extension is to feed time-lagged values into an FFNN:

- Time Delay Neural Networks (TDNNs) or NARX-style models use

- This is conceptually similar to autoregressive models but with nonlinear transformations.

- Time Delay Neural Networks (TDNNs) or NARX-style models use

- Limitations:

- The number of lags

- Long-range dependencies require very large

- The number of lags

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) address this by maintaining a hidden state that evolves with time, providing a more flexible way to capture history.

RNN Basic Formulation

- Vanilla RNN (many-to-one setup):

where:

- The network is unrolled over time during training, and backpropagation through time (BPTT) computes gradients with respect to all parameters.

- Loss function is typically an average over time or sequences:

Unrolling RNNs and Backpropagation Through Time

- During training, we often unroll an RNN across time steps:

- The recurrent cell is replicated for

- This yields a deep network whose depth equals the sequence length.

- The recurrent cell is replicated for

- Backpropagation Through Time (BPTT):

- We compute gradients by applying backpropagation on the unrolled network.

- Gradients at time

- Computational implications:

- Memory usage grows with sequence length, because we must store intermediate states.

- Truncated BPTT is often used, where gradients are propagated only for a fixed number of steps.

- Conceptually, RNN training faces similar challenges as very deep feedforward nets, but along the time dimension.

Vanishing and Exploding Gradients in RNNs

- In RNNs, gradients with respect to earlier time steps involve repeatedly multiplying by Jacobian matrices of the recurrent transition:

- If the largest singular value of these Jacobians is:

- Less than 1, gradients tend to vanish exponentially as

- Greater than 1, gradients can explode, causing numerical instability.

- Less than 1, gradients tend to vanish exponentially as

- Consequences:

- Vanilla RNNs struggle to learn long-term dependencies, focusing mostly on recent information.

- Mitigation strategies:

- Architectural changes (LSTM, GRU) that introduce better gradient flow.

- Gradient clipping to control exploding gradients.

- Careful initialization and activation choices.

Application · Forecasting the Equity Premium: Mind the News! (Adämmer & Schüssler, 2020, RoF)

- Problem

- Can news-based information improve forecasts of the monthly U.S. equity premium beyond standard macro–financial predictors?

- How important is the time-varying information flow from news relative to traditional predictors?

&

Market Events"] Embed{{"Embedding

(BERT / Word2Vec)"}} %% =========================== %% 2. 传统路径 (Aggregation) %% =========================== Agg["Monthly Aggregation

(Sum / Average Vectors)"] ML["Standard ML Model

(Ridge / RF / OLS)"] %% =========================== %% 3. 深度序列路径 (Advanced) %% =========================== subgraph DeepSeq [High-Frequency / Sequence Approach] direction TB %% 这一层代表不压缩,直接处理序列 Note[("Preserve Sequence

No Aggregation")] DL_Model[["RNN / LSTM

OR

Attention (Transformer)"]] end %% =========================== %% 4. 最终输出 %% =========================== Target(("Equity Premium

Prediction")) %% =========================== %% 连接逻辑 %% =========================== %% 主流程 News ==> Embed %% 路径 A:传统方法 (实线) Embed --> Agg Agg --> ML ML --> Target %% 路径 B:深度方法 (虚线) %% 从Embedding直接跳过Aggregation Embed -.-> Note Note -.-> DL_Model DL_Model -.-> Target %% =========================== %% 样式美化 %% =========================== %% 文本数据:黄色 style News fill:#fff9c4,stroke:#fbc02d,stroke-width:2px %% 向量化:青色 style Embed fill:#e0f7fa,stroke:#006064 %% 传统路径节点 style Agg fill:#e1bee7,stroke:#7b1fa2 style ML fill:#e1bee7,stroke:#7b1fa2 %% 深度路径 (虚线框区域) style DeepSeq fill:none,stroke:#f44336,stroke-width:2px,stroke-dasharray: 5 5 style DL_Model fill:#ffcdd2,stroke:#d32f2f,rx:5 style Note fill:#ffebee,stroke:none,color:#d32f2f %% 目标:绿色 style Target fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#2e7d32,stroke-width:2px

- Model / Algorithm

- Construct rich news-based predictors from large news databases (counts, sentiment, topic indicators, surprise measures), aligned at monthly frequency.

- Compare traditional predictive regressions with flexible ML methods (e.g., tree-based models, regularized regressions) that incorporate both standard predictors and news variables.

- Key Results

- News-based variables significantly improve out-of-sample forecasts of the equity premium relative to models using only macro and financial predictors.

- Gains are robust across evaluation windows and different ML specifications, highlighting the incremental value of a high-dimensional information flow extracted from news.

- Why this motivates deep sequence models

- News arrive as a time-ordered sequence of text and events, with possible persistence, decay and interactions with the macro–financial state.

- Current implementations often compress this rich sequence into static monthly features; RNNs/LSTMs and attention-based models are natural tools to capture how the timing, ordering and accumulation of news affect risk premia over multiple horizons.

LSTM and GRU Formulation (Core Equations)

-

LSTM cell (core idea; biases omitted for brevity):

-

GRU cell (simplified):

-

Gates decide what to forget, what to update, and what to output, helping with long-term dependencies.

LSTM Cell Intuition

- The Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) cell introduces a cell state

- Forget gate

- Input gate

- Output gate

- Forget gate

- The key idea:

- The cell state provides a highway along which information and gradients can flow across many time steps, with gates modulating updates.

- This helps preserve long-term information while still allowing the network to forget irrelevant history.

- In financial sequences, LSTMs can learn to “remember” important regimes or events and “forget” noise.

GRU Cell Intuition

- The Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) simplifies the LSTM by merging some gates and removing the explicit cell state:

- Update gate

- Reset gate

- Update gate

- The hidden state update is:

so the update gate interpolates between old state and new candidate. - Intuition:

- GRUs have fewer parameters and a simpler structure than LSTMs, often performing similarly in practice.

- They provide a learned balance between remembering past and incorporating new observations.

- In finance, GRUs can be attractive when model size and training speed are concerns.

Stacked and Bidirectional RNNs

- Stacked RNNs:

- Use multiple recurrent layers on top of each other.

- Lower layers capture simpler short-term patterns; higher layers capture more abstract and longer-term dynamics.

- Bidirectional RNNs:

- Process sequences in both forward and backward directions.

- The final representation at each time step concatenates information from past and future.

- In offline settings (e.g., risk assessment over historical windows), bidirectional models can exploit the entire sequence.

- In online prediction (e.g., trading), only past information is available, so we typically use unidirectional architectures.

- Deeper and bidirectional RNNs can improve performance but increase computational cost and risk of overfitting.

Intuition, Pros & Cons, Finance Use Cases

Intuition

- Hidden state

- Vanilla RNN can, in principle, represent complex sequence functions, but gradient propagation across many time steps is difficult.

- LSTM/GRU add paths where gradients can flow more easily (via cell state

Pros vs Cons

| Aspect | Pros | Cons / Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence | Natural for time series and sequences | Hard to parallelize across time |

| Memory | Can capture medium/long-term dependencies | Still struggles with very long range |

| Flexibility | Many variants (stacked, bidirectional) | Many hyperparameters, tuning heavy |

Finance uses:

-

Forecasting returns, volatility, or risk measures based on past time series.

-

Modeling order book dynamics and execution cost profiles.

-

Multi-step forecasting of macro-financial variables.

Summary

-

RNNs are designed for sequence data, with a hidden state that evolves over time as new inputs arrive.

-

Vanilla RNNs are conceptually simple but face optimization issues for long sequences.

-

LSTM and GRU introduce gating mechanisms to help retain or forget information, improving the modeling of medium to long-term dependencies.

-

In finance, RNN-based architectures are natural choices whenever temporal dynamics and history dependence are central.

-

Compared with CNNs, RNNs emphasize ordered dependence over time rather than local patterns in a fixed grid; again, the network structure encodes what kind of regularity is easiest to learn.

Part 5 · Attention Mechanisms (pre-Transformer)

Motivation

- Even LSTM/GRU may struggle when:

- Sequences are very long.

- The relevant information at time

- Attention mechanisms allow models to focus selectively on parts of an input sequence (or set) when making predictions.

- We focus on pre-Transformer attention:

- Encoder–decoder frameworks with attention (Bahdanau-style, Luong-style).

- Global attention over encoder hidden states.

- In finance, the idea of attention is useful when predicting an outcome from a sequence where only certain time intervals or events are especially informative (e.g., crisis periods, announcements, regime shifts).

Attention Basic Formulation

- Suppose we have encoder hidden states

- For a decoder state

- Scores:

where - Attention weights via softmax:

- Context vector as weighted sum:

- Scores:

- The context

Intuition and Variants

- Intuition:

- Instead of compressing all past information into a single vector, attention allows the model to look back at all encoder states and assign relevance weights.

- The softmax ensures weights are positive and sum to one, which can be viewed as a probability distribution over positions.

- Variants:

- Additive attention (Bahdanau):

- Multiplicative/dot-product attention (Luong):

- Global vs local attention:

- Global: attends over all positions.

- Local: attends over a window or subset.

- Additive attention (Bahdanau):

- Pre-Transformer attention is typically used on top of RNNs, not as a standalone sequence model.

Pros, Cons, and Finance Uses

Pros vs Cons

| Aspect | Pros | Cons / Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Long-range | Better handles long-range dependencies | Adds complexity and parameters |

| Interpret. | Weights |

Not always truly causal/explanatory |

| Flexibility | Works with RNN encoders/decoders, sets, etc. | Still sequence-length dependent |

- Finance-oriented uses:

- Focusing on important historical windows when forecasting risk or returns (e.g., crisis episodes, recent shocks).

- Combining multiple sources of sequential information (e.g., different horizons, different markets) by attending over their representations.

- Although modern practice often uses Transformer-based self-attention, the pre-Transformer attention ideas already clarify how models can adaptively weight past information.

Example: Sequence-to-Sequence with Attention

- In a standard encoder–decoder setup:

- An encoder RNN reads the input sequence and produces hidden states

- A fixed-size summary (e.g., the last hidden state) is passed to a decoder RNN that generates outputs.

- An encoder RNN reads the input sequence and produces hidden states

- This bottleneck can be problematic for long or information-rich sequences.

- Adding attention:

- At each decoding step, the decoder computes attention weights over all encoder states and forms a context vector

- The output then depends on both the current decoder state and

- At each decoding step, the decoder computes attention weights over all encoder states and forms a context vector

- Intuitively, attention allows the model to look back at different parts of the input sequence when generating each output.

- In finance, similar ideas can be used to forecast based on long historical windows while focusing on relevant subperiods (e.g., crisis episodes).

Summary

-

Attention mechanisms augment sequence models (typically RNNs) with the ability to selectively focus on different parts of the input.

-

Technically, attention computes similarity scores between a “query” state and a set of “key–value” states, turning them into weights used to form a context vector.

-

Pre-Transformer attention arose in encoder–decoder architectures and remains a useful conceptual tool for designing finance models that handle long and complex sequences.

-

In later lectures (on big data and large language models), we will revisit attention in the context of Transformers; here we focus on its core idea and pre-Transformer form.

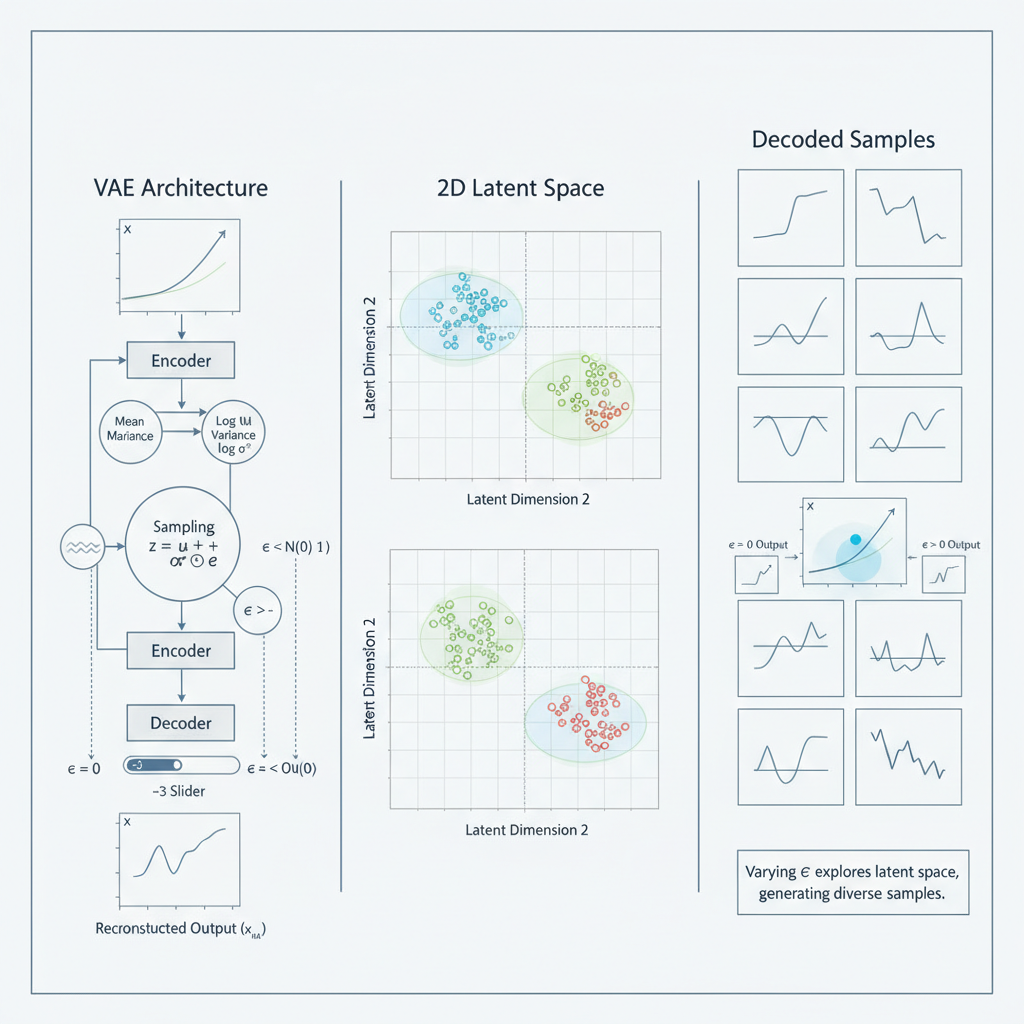

Part 6 · Generative Models: VAE and GAN

Motivation

- So far we focus on models that predict labels given inputs.

- Generative models instead aim to model the data distribution itself and generate new realistic samples:

- Scenario generation for risk management and stress testing.

- Synthetic data for backtesting or robustness analysis.

- Deep generative models also perform representation learning:

- Variational Autoencoders (VAE) learn low-dimensional latent variables that summarize financial states.

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) train a discriminator that implicitly learns features distinguishing typical from atypical market conditions.

- In finance, these models therefore play a dual role:

- They generate plausible scenarios consistent with historical data.

- They learn rich internal representations of complex joint dynamics, which can be reused for downstream tasks.

VAE Formulation (Core Ideas)

|

|

VAE Key Takeaways

-

VAEs posit a latent-variable model

-

Training maximizes a variational lower bound (ELBO) that balances:

- Reconstruction quality via

- Regularization via

- Reconstruction quality via

-

The reparameterization trick enables gradient-based optimization.

-

The encoder computes a low-dimensional latent representation of financial observations (e.g., yield curves, market states, portfolios), which can be used even without sampling from the decoder.

-

Thus, VAEs provide both a generative model for scenarios and a tool for nonlinear dimension reduction and representation learning.

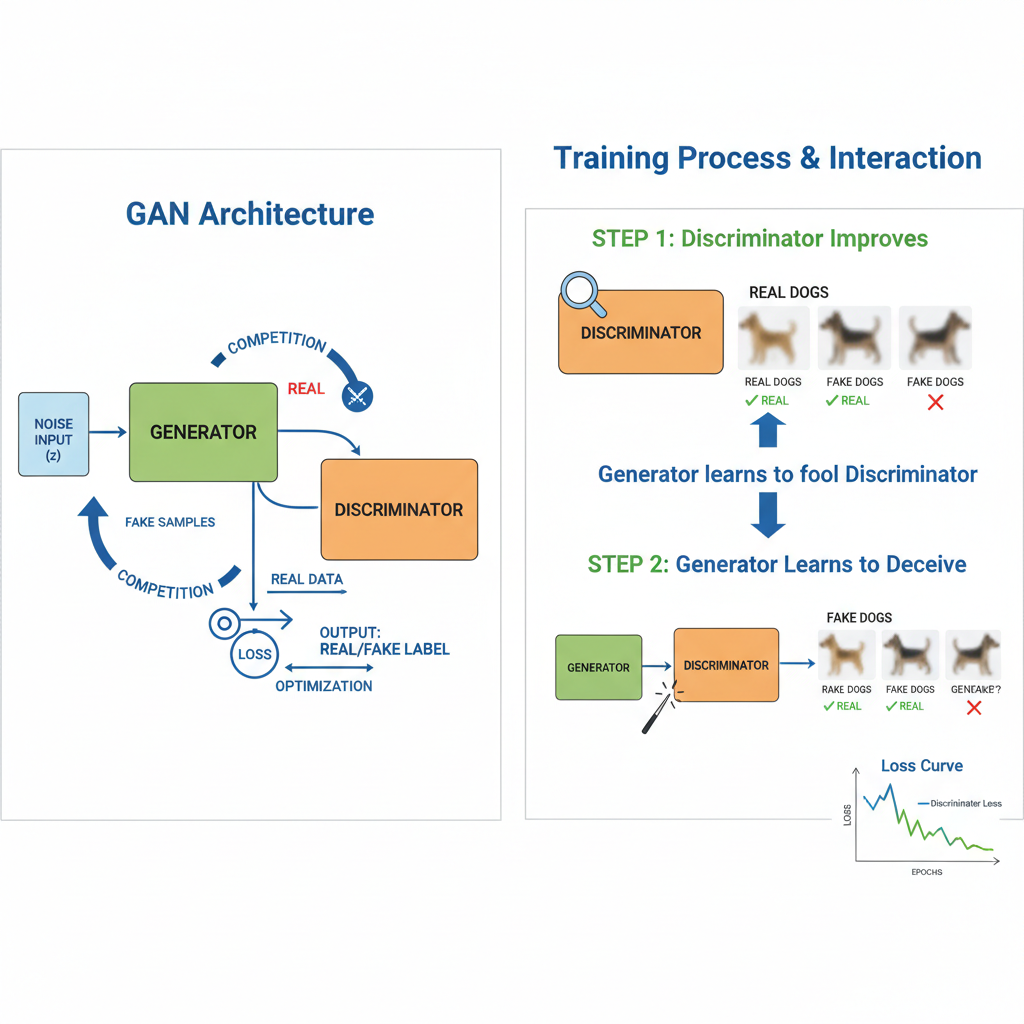

GAN Formulation (Core Ideas)

|

|

GAN Key Takeaways

-

GANs set up a two-player game between:

- A generator

- A discriminator

- A generator

-

The minimax objective encourages the generator to match the real data distribution and the discriminator to become a powerful classifier.

-

Practical training uses variants (e.g., Wasserstein GAN) to improve stability and reduce mode collapse.

-

In finance, GANs can generate realistic joint scenarios of returns, volatilities, or yield curves for stress testing and data augmentation.

-

The discriminator also acts as a representation learner: its internal layers learn features that distinguish typical from atypical patterns in markets, which can sometimes be reused for risk monitoring or anomaly detection.

Pros, Cons, and Finance Uses

Pros vs Cons

| Model | Pros | Cons / Risks |

|---|---|---|

| VAE | Probabilistic, explicit latent structure | Reconstructions may be too “smooth” |

| GAN | Sharp, realistic samples | Training instability, mode collapse |

- Finance uses:

- Scenario generation: simulate plausible joint paths of returns, volatilities, or yield curves under different regimes.

- Stress testing: generate rare but coherent combinations of shocks for risk management.

- Synthetic data: augment limited historical datasets while roughly preserving dependence structure.

- Market microstructure: simulate order flow or limit order book snapshots.

- These models can complement traditional stochastic models, but must be validated carefully to avoid misleading risk assessments.

Summary

-

VAEs and GANs are central deep generative models that learn to approximate complex data distributions.

-

VAEs use a probabilistic latent-variable framework and optimize an ELBO via an encoder and decoder.

-

GANs frame generation as a two-player game between a generator and a discriminator.

-

In finance, they are primarily useful for scenario generation, stress testing, and data augmentation, not as direct replacements for structural models or risk factor frameworks.

Application · Synthetic Data in Finance (Potluru et al., 2024)

- Problem

- Survey and evaluate how synthetic data can be used in finance: for model development, backtesting, stress testing, and privacy-preserving data sharing.

- Identify where synthetic data add value, what risks they introduce, and how to design them responsibly.

- Model / Algorithm

- Review a broad range of generative approaches, including:

- Classical parametric and copula-based simulation methods;

- Deep generative models such as GANs, VAEs, and time-series GAN variants for returns, limit order books, and other financial time series.

- Discuss design choices (conditioning on scenarios, domain constraints, evaluation metrics) that are critical for financial applications.

- Review a broad range of generative approaches, including:

-

Key Results / Insights

- Synthetic data can augment scarce or sensitive datasets, enabling more robust model training and more extensive backtesting, especially for rare events and stressed regimes.

- They support privacy and regulatory compliance by allowing institutions to share realistic but non-identifying data.

- However, poorly designed generators can misrepresent tail risks or dependence structures, leading to misleading risk assessments; careful validation and domain knowledge are essential.

-

Why suitable for deep generative models

- Financial data are high-dimensional, noisy, and exhibit nonlinear dependence (volatility clustering, heavy tails, cross-sectional correlations) – a natural domain for GANs and VAEs that can approximate complex joint distributions without rigid parametric forms.

- Combining deep generative models with economic constraints offers a promising path to realistic yet controllable scenario generators for risk management and trading.

Application · Generating Synergistic Alpha Collections via RL (Yu et al., 2023)

-

Problem

- Quant researchers often design thousands of formulaic alpha signals (functions of prices, volumes, fundamentals, etc.).

- This paper asks: can we use reinforcement learning (RL) to automatically generate a collection of alpha formulas that are individually useful and synergistic when combined into a portfolio?

-

Model / Algorithm

- Define a large, structured “alpha space” (building blocks such as arithmetic operations, lags, rankings, cross-sectional operators).

- Use deep RL to model an “alpha engineer” agent that sequentially constructs or selects alpha formulas; the environment evaluates each proposal by simulated (or historical) backtest performance and diversification properties.

- The reward balances predictive power, robustness and correlation structure, pushing the agent toward sets of complementary alphas rather than a single best signal.

(Features/Signals)"] RLAgent["RL Agent

(Policy Network)"] CandidateAlpha["Candidate Alpha Formulas

(Structured Outputs)"] BacktestEnv["Backtest Environment

(Simulated Trading)"] Reward["Reward Signal"] PolicyUpdate["Policy Update"] %% =========================== %% 连接逻辑 %% =========================== AlphaBlocks --> RLAgent RLAgent --> CandidateAlpha CandidateAlpha --> BacktestEnv BacktestEnv --> Reward Reward --> PolicyUpdate %% =========================== %% 公式树结构 (Alpha 组成块) %% =========================== subgraph AlphaTree["Alpha Formula Tree"] direction TB node1["Alpha Component 1"] node2["Alpha Component 2"] node3["Alpha Component 3"] node1 --> node2 node1 --> node3 %% 示例公式,注意层次结构 Formula1[("Alpha = f(Component1, Component2, Component3)")] node1 --> Formula1 node2 --> Formula1 node3 --> Formula1 end %% =========================== %% 样式美化 %% =========================== %% Alpha 结构:蓝色 style AlphaBlocks fill:#bbdefb,stroke:#2196f3,stroke-width:2px %% RL Agent:紫色 style RLAgent fill:#e1bee7,stroke:#8e24aa %% 候选 Alpha 公式:橙色 style CandidateAlpha fill:#fff3e0,stroke:#ef6c00 %% 回测环境:绿色 style BacktestEnv fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#2e7d32 %% 奖励:红色 style Reward fill:#ffebee,stroke:#c62828,stroke-width:2px %% 策略更新:黄色 style PolicyUpdate fill:#fff9c4,stroke:#fbc02d %% 公式树(公式结构) style AlphaTree fill:#f3e5f5,stroke:#7b1fa2,stroke-dasharray: 5 5

-

Key Results

- RL-generated alpha collections achieve higher portfolio Sharpe ratios and more stable performance than naïve or manually curated formula sets built from the same building blocks.

- The learned alphas exhibit non-obvious combinations and transformations of basic signals, illustrating that the search space is too large for manual trial-and-error.

-

Why this is a natural deep/RL problem

- The alpha design space is combinatorially huge and structured; it is natural to frame it as a sequential decision problem where each step adds an operator or modifies a formula.

- Deep RL can learn to generate structured objects (alpha formulas, alpha sets) under noisy long‑horizon rewards—an instance of “generative modeling for strategies” rather than just data.

Part 7 · Graph Neural Networks (GNN)

Motivation

- Many financial systems are naturally represented as graphs:

- Interbank lending and exposure networks.

- Ownership and control links among firms and funds.

- Supply-chain networks and trade relationships.

- Traditional approaches often compress graphs into hand-crafted features (degrees, centrality measures).

- GNNs take a different approach: the graph structure itself guides learning.

- Nodes aggregate information from their neighbors through message passing.

- After several layers, node representations capture multi-hop relational information.

- This inductive bias makes GNNs suitable when who is connected to whom and how strongly matters for outcomes such as default, contagion, or spillovers.

Message Passing Formulation

- A typical message passing GNN layer updates node features

- Message aggregation from neighbors:

where

2. Node update: - In Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN), a simplified form is:

where:

Intuition, Pros & Cons, Finance Uses

Intuition

- Each GNN layer allows nodes to exchange information with their neighbors.

- After

- This resembles iterative contagion or diffusion, but with learned aggregation and transformation functions.

Pros vs Cons

| Aspect | Pros | Cons / Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Respects network topology | Needs graph data and quality edges |

| Flexibility | Learns complex neighborhood interactions | Over-smoothing for many layers |

| Finance | Natural for systemic risk, contagion, spillover | Interpretability can be challenging |

Finance uses:

-

Systemic risk: predict default probabilities or losses using interbank networks.

-

Credit risk: incorporate supply-chain or ownership networks.

-

Market structure: model spillovers among firms or sectors linked by customer–supplier relationships.

Summary

-

GNNs generalize neural networks to graph-structured data via message passing and aggregation over neighbors.

-

They learn representations of nodes, edges, or entire graphs that implicitly capture network structure and interactions.

-

In finance, GNNs are promising tools for modeling interconnected systems, such as banking networks, ownership structures, and supply-chain relationships.

-

Compared with MLPs on tabular data, GNNs encode a strong prior that outcomes depend critically on relations rather than only on standalone characteristics.

-

Again, network architecture shapes what is easy to learn: with a graph structure, the model is biased toward capturing relational patterns and contagion effects.

Part 8 · Practical Issues & Summary

- Optimization for Deep Networks

- Regularization, Overfitting, and Explainability

- Overall Summary and Outlook

Optimization for Deep Networks

- Deep networks are trained using stochastic gradient-based methods:

- SGD:

where - Momentum, RMSProp, Adam: adaptive or momentum-based variants.

- SGD:

- Practical considerations:

- Learning rate scheduling (decay, warm restarts, etc.).

- Batch size: trade-off between stability and generalization.

- Initialization (Xavier/He) and normalization (batch norm, layer norm) can improve convergence.

- In finance, optimization must balance:

- Predictive performance.

- Stability across rolling windows.

- Robustness to distribution shifts (regime changes, crises).

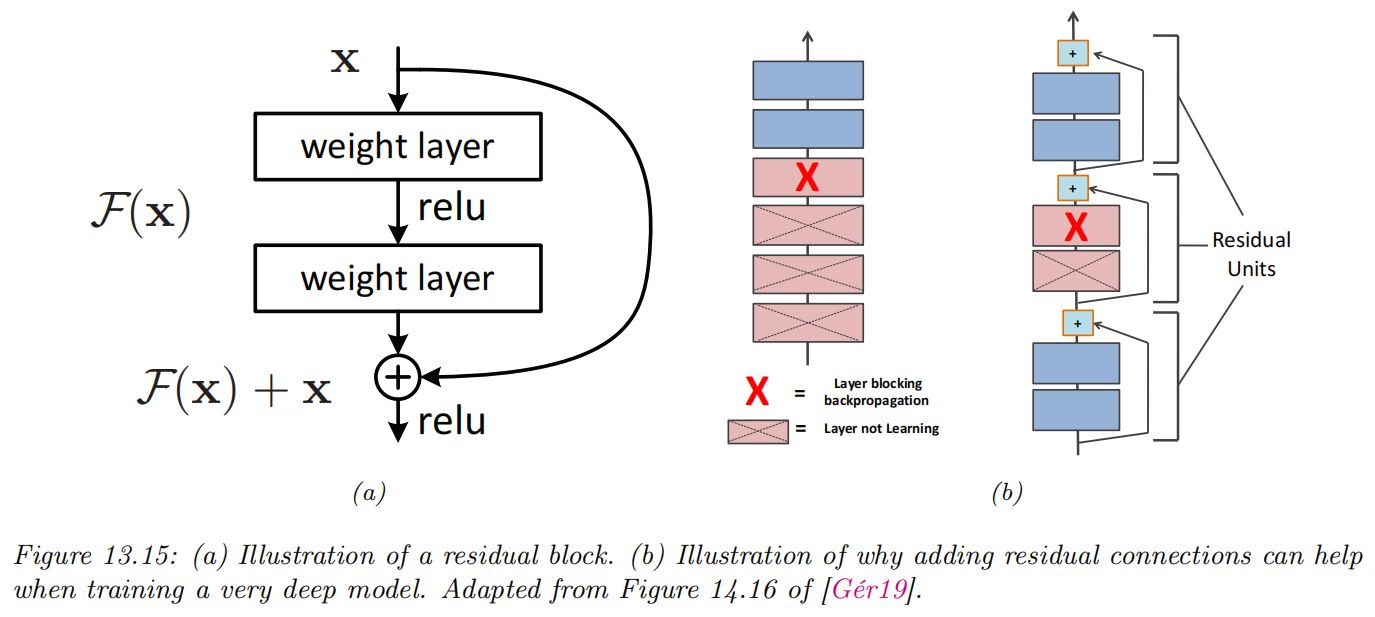

Vanishing / Exploding Gradients in Deep Networks

- Deep feedforward and recurrent networks share a common challenge:

- Gradients are propagated through many layers (or time steps), each involving multiplication by weight matrices and application of nonlinearities.

- If the effective Jacobians tend to contract, gradients vanish; if they tend to expand, gradients explode.

- Practical symptoms:

- Training loss stops decreasing or becomes extremely unstable.

- Early layers or early time steps receive almost no learning signal.

- Mitigation strategies:

- Use non-saturating activations (e.g., ReLU family) instead of sigmoid/tanh in hidden layers.

- Careful initialization (e.g., Xavier, He) and proper normalization layers.

- Gradient clipping, especially for RNNs.

- Architectural changes such as residual connections, which provide shortcuts for gradient flow.

Residual Connections to Ease Optimization

- Residual networks (ResNets) introduce skip connections between layers:

- Instead of learning a mapping

- Instead of learning a mapping

- Benefits:

- If the optimal mapping is close to identity, learning the residual

- Gradients can flow directly through the skip connection, reducing vanishing gradient issues in very deep networks.

- If the optimal mapping is close to identity, learning the residual

- Although originally developed for image CNNs, residual ideas are widely used in:

- Deep MLPs for tabular data.

- Deep sequence models.

- In finance, residual connections can help train deeper architectures that capture complex interactions, while keeping optimization stable.

Regularization in Deep Networks

- Deep models have many parameters and are prone to overfitting, especially in financial datasets with limited effective sample size.

- Common regularization strategies:

- Weight decay: L2 penalty on weights, equivalent to a Gaussian prior in a Bayesian view.

- Early stopping: monitor validation performance and stop training when it starts to deteriorate.

- Dropout: randomly zero out a fraction of units during training, forcing the network to learn more robust representations.

- Additional techniques:

- Data augmentation when applicable (e.g., slight perturbations of inputs).

- Ensemble methods (averaging predictions of multiple trained models).

- Effective regularization is essential for models to generalize across market regimes rather than just fitting historical noise.

Bayesian View of Neural Networks (Very Brief)

- In a Bayesian interpretation, network weights are treated as random variables with prior distributions:

- For example, weight decay corresponds to a Gaussian prior on weights.

- Instead of a single point estimate

- Predictions integrate over parameter uncertainty:

- Exact Bayesian neural networks are computationally challenging, but:

- Approximate methods (e.g., variational inference, dropout-as-Bayesian) provide uncertainty estimates.

- For finance, a Bayesian perspective highlights parameter uncertainty and predictive uncertainty, which are important for risk management and decision-making under uncertainty.

Regularization, Overfitting, and Explainability

- Deep models have many parameters, so regularization is critical:

- Weight decay (L2 penalty on weights).

- Dropout: randomly zeroing activations during training to prevent co-adaptation.

- Early stopping: monitor validation loss and stop before overfitting.

- Data augmentation (where meaningful for financial data).

- Overfitting in finance is particularly dangerous because:

- Sample sizes are often smaller than in internet applications.

- Markets and regimes change over time, leading to nonstationarity.

- Explainability:

- Feature importance via perturbation or gradient-based attribution.

- Comparing deep outputs with simple benchmarks (linear models, trees).

- For regulated contexts (credit, consumer finance), simpler models may still be preferred despite deep learning’s flexibility.

Hybrid Architectures in Finance

- In practice, many successful deep learning systems in finance are hybrid architectures:

- CNN + LSTM:

- CNN extracts local patterns from structured inputs (e.g., limit order book snapshots, term-structure slices).

- LSTM models the temporal evolution of these extracted features.

flowchart LR %% LOB 图像到价格影响预测的过程 LOB["LOB Images

(Limit Order Book)"] CNN["CNN Layer<br/(Feature Extraction)"] LSTM["LSTM Layer

(Temporal Modeling)"] PriceImpact["Price Impact Forecast"] %% 连接逻辑 LOB --> CNN CNN --> LSTM LSTM --> PriceImpact %% 样式美化 style LOB fill:#bbdefb,stroke:#2196f3,stroke-width:2px style CNN fill:#e1bee7,stroke:#8e24aa style LSTM fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#2e7d32 style PriceImpact fill:#ffebee,stroke:#c62828,stroke-width:2px - GNN + MLP/RNN:

- GNN aggregates information over financial networks (exposures, ownership, supply chains).

- MLP or RNN maps node embeddings into predictions (default probabilities, volatility, losses).

flowchart LR %% 供应链图到违约/收益预测的过程 SupplyChain["Supply-Chain Graph

(Graph Structure)"] GNN["Graph Neural Network

(Node Embedding)"] FirmEmbedding["Firm Embedding

(Feature Vector)"] MLP_RNN["MLP / RNN Layer

(Prediction Model)"] DefaultReturn["Default / Return Prediction"] %% 连接逻辑 SupplyChain --> GNN GNN --> FirmEmbedding FirmEmbedding --> MLP_RNN MLP_RNN --> DefaultReturn %% 样式美化 style SupplyChain fill:#fff9c4,stroke:#fbc02d,stroke-width:2px style GNN fill:#ffe0b2,stroke:#ff9800 style FirmEmbedding fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#2e7d32 style MLP_RNN fill:#f3e5f5,stroke:#8e24aa style DefaultReturn fill:#ffebee,stroke:#c62828,stroke-width:2px

- CNN + LSTM:

- These combinations leverage different inductive biases:

- Convolution for local patterns.

- Recurrence for temporal dependence.

- Graph structure for network effects.

- When designing a model, think in terms of which architecture fits which part of the data, rather than searching for a single “best” deep model.

When to Use Deep Learning in Finance (and When Not)

- Deep learning is useful when:

- We have large datasets with rich cross-sectional and/or temporal variation.

- Relationships are highly nonlinear and difficult to capture with simple models.

- The main goal is predictive performance, and interpretability requirements are moderate.

- Inputs have complex structure (sequences, networks, high-frequency microstructure data).

- It is less attractive when:

- Sample size is small, or effective data size is limited by regime shifts and structural breaks.

- Regulatory or business constraints require high interpretability and transparency.

- Simple models (e.g., linear, tree-based) already achieve satisfactory performance.

- In the next lecture, we move from predictive modeling to decision-making (reinforcement learning), where model complexity must be balanced against stability, interpretability, and control.

Overall Summary and Outlook

- We introduced a toolkit of deep learning architectures for finance:

- MLP for general high-dimensional nonlinear prediction on tabular data.

- CNN for structured arrays and local patterns.

- RNN / LSTM / GRU for sequences and temporal dynamics.

- Pre-Transformer attention for selectively focusing on important parts of sequences.

- VAE / GAN for generative modeling and scenario simulation.

- GNN for networked and relational financial data.

- Across architectures, we emphasized:

- Core formulations and intuitions.

- Typical procedures for training.

- High-level pros/cons and finance applications.

- In the next lecture, we move from supervised learning with fixed data to Reinforcement Learning, where agents interact with dynamic financial environments (markets, portfolios, trading systems).